Cornwall Road, south of downtown Cary, holds a special place in Cary's African American history. From the mid-1800s and into the 1900s, it was home to many African Americans, some whose families settled on and began farming the land just after the Civil War. It also was the place where African Americans began worshiping under a brush arbor in 1868 on a site where they had begun to bury their loved ones. Now surrounded by newer homes and the Glenaire Retirement Community, a significant remnant of Cary's African American past still remains at 300 West Cornwall Road. The sacred land where families began burying their loved ones as early as 1866 is now a 1.39 acre cemetery owned and maintained by Cary First Christian Church. And it has some stories to tell . . .

Stories of leadership, service to country, enslavement, education, and more

When you step through the cemetery gate into Cary's African American past, you will find the resting places of the first African American businessman and community leader in Cary; founders of the new Cary Elementary School (for Colored Children); businessmen, farmers, and laborers; church founders, leaders, and supporters; community organizers; large land owners; educators; WWI, WWII, Korean, and Vietnam War veterans; free and formerly enslaved African Americans and people of mixed race. You will see grave sites of prominent families and grave sites of unknown persons. And you will walk upon ground where known and unknown persons are laid to rest with no grave marker to indicate where.

Seven members of the Committee for a New Elementary School in the Colored Community who were instrumental in establishing a school for African American children in 1937 after the Cary Colored School near the present day Cary Elementary School burned down are buried at Cary First Christian Church Cemetery (CFCCC): Arch Arrington, Jr., Willis Cotton, Mae Hopson, Effie Turner Jones, Emily Arrington Jones, Connie and Lillian Turner Reaves. The new Cary Elementary School (for Colored Children) went on to become present day Kingswood Elementary School.

[1].jpg) Cary Elementary School (for Colored Children) ca. 1937

Cary Elementary School (for Colored Children) ca. 1937

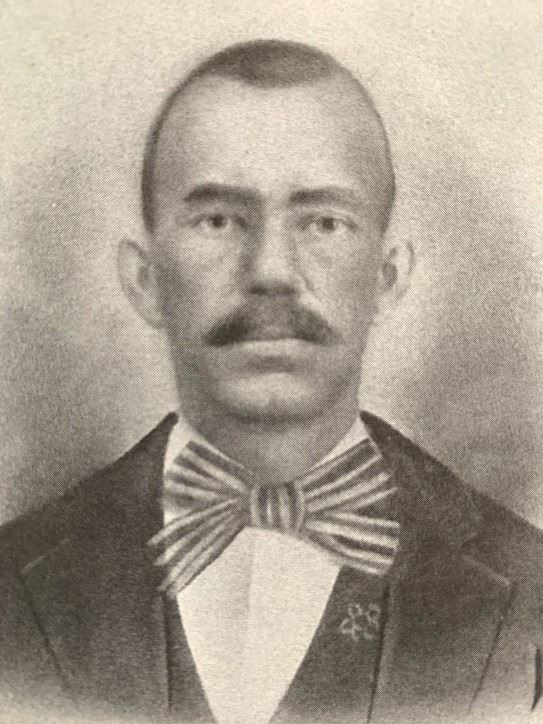

One of the most prominent families buried at CFCCC is the Arrington family. Patriarch Alfred Arrington has the earliest marked birth date in the cemetery: 1829. He was the son of an enslaver on a plantation in Warren County, North Carolina where he learned many trades. Alfred was freed before the Civil War came to Cary during the late 1860s. Both he and his son Arch Arrington, Sr. were craftsmen and became large landowners in north central Cary. Arch, Sr. was one of the first African American businessmen and community leaders in Cary. He married Sallie Blake, sister of John Addison Blake, the founder of the Union Bethel African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church on North Academy Street in Cary.

Arch Arrington, Sr.

Sallie Blake ArringtonArch and Sallie's son Arch Arrington, Jr. organized the African American community to build a new school for African American children in 1937 after the Cary Colored School near the present day Cary Elementary School burned down. Arch, Jr.'s brother Goelet Arrington and sister Emily

donated the land to the Wake County School System for the school, which went on to become Kingswood Elementary School, located today at 200 East Johnson St.

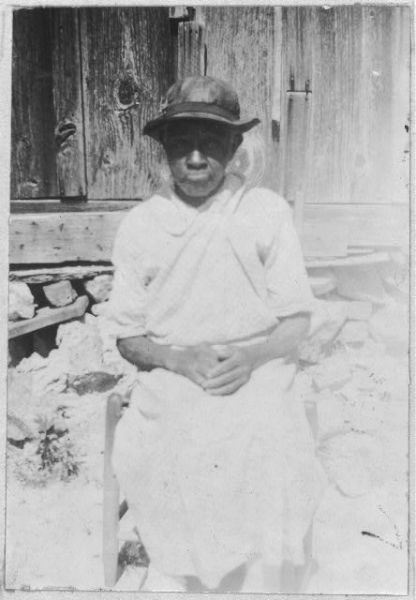

2300 formerly enslaved persons were interviewed and their memories recorded as part of the Federal Writers Project that produced U.S., Interviews with Former Slaves, 1936-1938. Three of them are buried in Cary at CFCCC: Eliza Blake Nichols, Martha Jones Organ (unmarked grave), and Chaney Utley Hews (unmarked grave).

Eliza Blake Nichols

(Photo from Library of Congress, Manuscript Division)

One of the earliest marked graves in the cemetery is that of Jennie Beckwith, who died in 1896 at the age of 31. She was the first wife of John Beckwith, who was born into enslavement in Cary and was 9 years old when the Civil War ended. His memories were also recorded in U.S., Interviews with Former Slaves, 1936-1938. John was a farmer and later a beloved custodian at Cary High School when it was located on Academy St. He was remembered for ringing the bell, signalling to students that they should all be in their seats in their classrooms. John is buried in an unmarked grave at Wake County Home Cemetery off Noble Road near Five Points in Raleigh. Several other Beckwith family members are buried at CFCCC in unmarked graves.

One fourth of the 86,000 troops from North Carolina in WWI were African American. Seven WWI and three WWII veterans are buried at CFCCC, along with one Korean War veteran and two Vietnam War veterans. WWI veterans: Exum Arrington, William Boyd (unmarked grave), Clarence Cotton, James A. Cotton, Harry Jones, Herman Lee, Arthur Moore. WWII Veterans: Clyde Louis Arrington, Fletcher Beckwith, Bruce Jones. Korean War Veteran: Emerson “Dick” Arrington. Vietnam War Veterans: Archie Wayne Jones, Edgar B. Jones.

Bruce Jones, WWII Veteran

The earliest marked grave in the cemetery is that of little Hattie Turner, who died as an infant in 1891. She was the daughter of Bob and Lucy Turner. Sadly, 10 infants are buried at CFCCC.

Caring for the cemetery

During 2021, members of Cary First Christian Church partnered with the Town of Cary and the Friends of the Page-Walker Hotel to take steps to make the public aware of the significance of this historic cemetery, the first cemetery to be designated as a landmark in Cary and in all of Wake County. The Town planted new trees and helped clean up the cemetery and also enlisted Verville Interiors & Preservation to repair some of the damaged headstones. Volunteers from the church worked with volunteers from the Friends of the Page-Walker to research the history of the cemetery and the people who are buried there and to produce a walking tour brochure, which is now available outside the gate of the cemetery. The refurbished cemetery along with the brochure were revealed at a ribbon-cutting ceremony on October 30, 2021.

Not the first time the cemetery received some love and attention

It's possible the cemetery would not be standing in its original location today if not for the efforts of church member Sallie Jones. Sallie, a descendant of historic Cary African American families including the Arringtons and the Blakes, made it her personal project in the 1980s to preserve the Cary First Christian Church Cemetery to save it from being lost. She hired archeologists to survey the cemetery and produce a map of marked and unmarked graves and she enlisted the help of the community to clean up and restore the cemetery, which had fallen into disrepair through overgrowth of vegetation and some vandalism. Desiring to honor those unknown persons buried in unmarked graves, Sallie worked with experts at the state level to identify some of the unknown names, spending many hours going through archived records. In a critical step, she registered the cemetery with the state, protecting it from ever being sold. Sallie Jones, today at age 96, was a key contributor to the development of the newly released walking tour brochure through her knowledge and remarkable memory of the people buried at the cemetery.

Sallie Jones

Sallie Jones

Formerly unknown people buried in the cemetery now identified

The cemetery holds approximately 262 burials as of 2021. Of these 262 burials, around 102 known persons are buried in graves with markers that display names and dates. About 160 persons are buried in graves either unmarked or marked with boulders, piles of stones, quartz, and uninscribed or unreadable stone, concrete, marble, and granite. Some are buried in graves marked with uninscribed concrete slabs placed by the church after the archeological survey revealed that 139 of the 160 unmarked graves had been unknown until 2002. The vinyl stickers seen on these grave markers correspond to locations on a map produced by the archeological survey. Through the tireless efforts of church member Sallie Jones and additional research by church volunteers and the Friends of the Page-Walker, 113 of the people buried in unmarked graves or graves with unreadable markers have been identified. 47 unknown persons still remain to be identified.

A look at the land in the 1860s and its subsequent history

Stories passed down tell that African Americans began burying their loved ones on the land as early as 1866. Research revealed that the land belonged to James Allen at the time, a white man living in Wake County, who then sold it to Mariah Seagroves Horton and her husband William, also both white and of Wake County. Interestingly, the Hortons sold the land to James Joseph (J. J.) Hines of Craven County in 1869. J. J. Hines was a white traveling minister who sometimes preached in Asbury. Ownership of the land stayed among white people of Craven County until 1879, but statements in deeds reveal that sometime between 1869 and 1877, J. J. Hines conveyed one acre of the 35+ acres he had purchased from the Hortons to a religious congregation, presumably the early members of Cary First Christian Church. In 1879, when Tranquilla and George Dowell of Wake County purchased the land, the deed contained this statement: “(excepting) nevertheless one acre of said tract at its north west corner on which a church has been built by certain colored (people) containing 34 1/2 acres more or less, after deducting said acre excepted.” The church structure to which this deed is referring might have been the brush arbor under which the early members of the Cary First Christian Church congregation worshiped from 1868 to 1883, when they moved into their church building on Holleman Street near present day Cary Elementary School. In 1909, George and Tranquilla, also white, conveyed a piece of land to “Trustees for Colored Cary Christian Church”: John Beckwith, Handy Jones, and Dennis Jones. The land in this deed increased the cemetery size to approximately 1.377 acres, the size that it is today. Handy Jones and Dennis Jones are buried at CFCCC. In 1968, the church moved to its current location at 1109 Evans Road. Today, the cemetery is the only vestige of the congregation at its original location.

Unique grave markers

The most unusual and historically significant grave marker in the cemetery is a rare segmental-arched wooden headstone, dating back possibly to the mid-1800s. There are no markings or engravings remaining on this wooden marker to enable us to know who is buried here. Many grave sites in the cemetery are marked by simple pieces of rock or boulders with no inscriptions, or are not marked at all. Though researchers have been able to identify 113 of the 160 people who are buried in unmarked or unreadable graves, it's likely that people who were buried before the late 1800s might never be identified because of the lack of records dating back to that period and because enslaved persons were often not accounted for by name but simply by the number of them that were enslaved by a land or property owner.

Many of the readable grave markers in the cemetery display funerary art, including cherubs and crowns, stars, clasping and praying hands, laurel branches, ivy vines, and engraved interlocking chains and letters such as “FLT” for Friendship, Love, and Trust that denote the deceased's affiliation with the Grand United Order of Odd Fellows (not to be confused with the International Order of Odd Fellows, whose constitution included a “whites only” clause until 1971).

Some of the grave markers are made of concrete. Family stories tell us that the African American Hawkins family made gravestones, along with the Satterfield family. Both families' homes were on West Cornwall Road, very near the cemetery. Though researchers have not been able to confirm it, it's possible the Hawkins and Satterfield families made some of the gravestones here.

A few of the gravestones are marked with hand-scratched inscriptions, including the gravestones of Nazareth Jones, Mattie Norris, and Rev. Boyd, one of the early ministers of Cary First Christian Church. One unusual set of stones represents not a grave marker, but rather a memorial marker. No bodies are buried with the stones, but one them contains a hand-scratched inscription: “In memory of Geo. W. Day and family.” A second engraved stone with the names of all the family members accompanies the hand-scratched stone. The George Washington Day family was originally from Orange County, where a large number of mixed race families migrated from Virginia in the early 1800s. Census records show they were living in Cary in 1880. Although further research is required, it's possible that this family is related, albeit distantly, to Thomas Day, the renowned furniture maker who left Virginia and settled in Milton, North Carolina in 1823.

Not the only African American cemetery in town

Many African Americans from the Cary community are buried in the private Turner-Evans Family Cemetery at 800 Old Apex Road in Cary. The Turner and Evans families owned large tracts of land in that area in the late 1800s and early 1900s. The Evans family owned and still owns a large amount of land to the west on Evans Road -- which is named for them -- and donated the land on which the Cary First Christian Church is currently located on Evans Road. Some members of the Turner and Evans families are buried in CFCCC and some members of the families buried at CFCCC are buried in the Turner-Evans Family Cemetery as a result of marriages between the two families.

Explore Cary's rich African American history

Take a walking tour of the Cary First Christian Church Cemetery with our new brochure (available at cemetery entrance). Trace Cary's African American history on a self-guided driving tour (download here) or follow along with a guide on one of our African American trolley tours (check here for availability). Stop by the front desk of the Page-Walker Arts & History Center to purchase a copy of Peggy Van Scoyok's book Desegregating Cary.

Help build a memorial to those buried in unmarked graves

Contribute to a fund to erect a simple memorial to known and unknown persons who are buried at Cary First Christian Church Cemetery in graves that are unmarked or graves that are marked with unreadable stones. Contact admin@caryfirst.org or call 919-467-1053 to learn how.